Scott McMaster: A Career Retrospective

Scott McMaster is the manager of the McMaster Accelerator Laboratory, a suite of facilities located in the Tandem Accelerator Building (TAB) on McMaster’s main campus. Recently, NO&F scientist Matt Moran had a chance to sit down with Scott to get his perspectives not only on the facilities he manages, but also his experiences as both a worker and manager in the same facility. In the second part of this two-part interview, Scott reflects on his career that spanned nearly forty years, and provides some insights and ideas that helped him navigate this complex and rewarding field.

So how did you originally get into working in nuclear at McMaster?

That’s a funny story. I actually wanted to be a pilot. I started flying at age 15 and by the time I started first year engineering at McMaster in 1978 I had my glider and commercial pilot’s licenses and was a flight instructor at Hamilton airport. I quit engineering to try and make a go of it in the aviation industry, but jobs were scarce, and the pay wasn’t great unless you could get on board with a commercial airline. So, after a stint doing various flying jobs, and two years in air traffic control, I came back to McMaster part-time in Honours Physics in 1983 and then transferred to Engineering Physics. In 1985 I got a part time student operator job at the accelerator, then a full-time job as a research engineer with CEMD (Centre for Electrophotonic Materials and Devices, now CEDT, Centre for Emerging Device Technologies) doing molecular beam epitaxy – that’s thin-film deposition of single crystals to make semi-conductors. I had that job until McIARS (McMaster Institute for Applied Radiation Sciences) offered me the job as manager in 2000. By then I had finish both a B.Eng. and M.Eng.

You must have witnessed a lot of change in that time.

You don’t know the half of it. When I started, the facility was operated with large operating grants and had a large and diverse user group. But in the early 1990s there was a large shift away from the operating grant model, and the accelerator lost its grant in 1992. That was really a time of change in research funding at the national and provincial levels. There started to be more of an emphasis on having commercial or private sector tie-ins to help to fund both facilities and research.

What was the impact of that transition?

It definitely opened up the university to more opportunities. When I started here TAB was mostly empty. The last 25 years has seen a major investment in facilities with more concrete applications, like the cyclotron and generating isotopes to further radioimaging and radiotherapeutic medicine. But I think it is important that we don’t forget that we are an institution that was founded on the principle of basic research – the discovery of knowledge. My philosophy has always been “We’re here to write the answer book. We don’t necessarily know what the questions are.” As long as our partnerships and industry collaboration is kept in balance with keeping facility access affordable and accessible to people interested in fundamental research, we should be okay.

We’re here to write the answer book. We don’t necessarily know what the questions are.

What impact do you feel you had in the role?

Managing a facility is a lot like flying a plane: instead of concentrating on one thing, you have to keep your eye on many different systems and make sure they are working in harmony. I’d like to think I was able to successfully maintain the facility while balancing the demands of a diverse group of users, while at the same time training and mentoring a core group of personnel to help me achieve that.

Any wisdom gained over the years managing the facility?

I began to realize as I got comfortable in my position that being a good manager isn’t just about managing facilities. It’s about managing people. For example, when we first changed our model, we decided to charge researchers on a use-by-use basis. But all that achieved was to get researchers to come up with reasons not to use the facilities. When I implemented a charge for facility access on a yearly basis, suddenly researchers were coming up with reasons to use the facilities.

Being a good manager isn’t just about managing facilities. It’s about managing people.

Apart from the users, you also learn quickly how to effectively manage a team. As I leave, I’m trying to structure it so that instead of a successor, I can shift my responsibilities to members of my staff, to let them grow in their careers and to reward them for their hard work and diligence. I’ve also learned how to let them fail, how to give them the tools they need to do their job, and how to shield them from the bureaucracy so they have the time and energy to keep pushing us forward.

What about the people you worked with? Does anyone stand out?

That’s a hard question. Because to me, the answer is really “everyone.” Working at a university is an opportunity to work with the smartest, hardest-working, well-informed, and well-read people you could hope to find in a workplace environment. I can honestly say that my career has been enriched by all the people that I’ve had the privilege of working with over the years.

What do you plan to do in retirement?

Flying, and a lot of it. Not that I ever gave it up, mind you. I fly competition aerobatics and was named Canadian National Unlimited Champion in 2017. I also enjoy cave diving, sky diving, and scuba diving. Once I retire, I’ll have more time to dedicate to those pursuits.

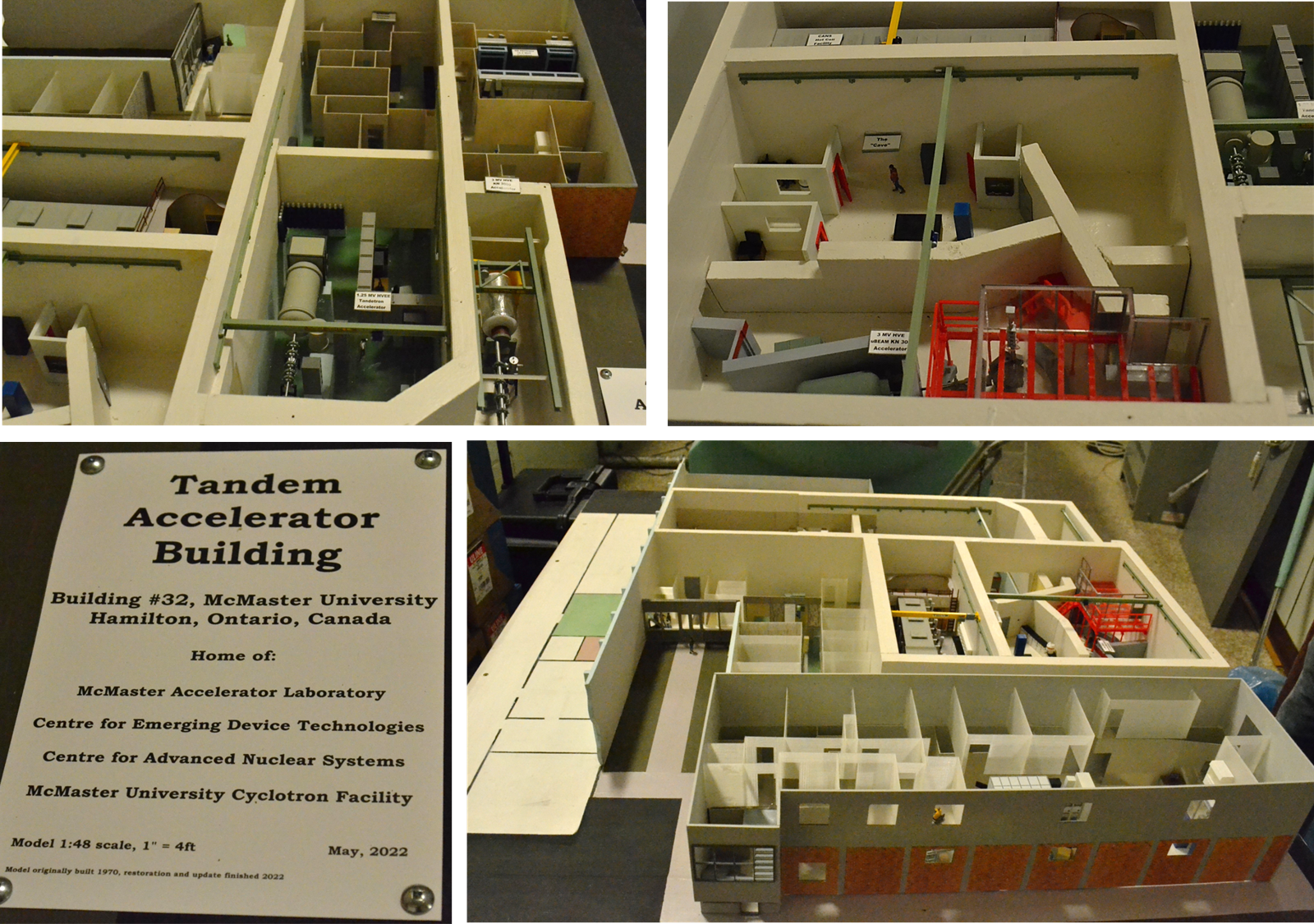

One last thing. I’ve heard that you’ve been building a scale model of the facility that you made yourself out of 3D printed components. Is it finished, and can I see it?

Of course! But for the record, I didn’t start it. There was an original model built from wood when I arrived, likely constructed during the design phase. I built around the original by adding 3D printed pieces to represent all the additions that have been made over the last fifty odd years. To me it’s not only about the facility but showing its evolution and capturing the history. I think a lot of where we hope to go can be gleaned from where we’ve been and what we’ve done to this point.

I think a lot of where we hope to go can be gleaned from where we’ve been and what we’ve done to this point.